Initially, I thought that dovetails or any joinery applied to an African door would be an oxymoron. Would they look way out of line for my shop altar? That is the question. Items crafted in Africa, especially ancient Africa, are considered primitive and rustic. There are a dearth of examples of furniture, cabinets, personal items, coffins, and other objects available for study by non-art historians.

“Civilians” are rarely afforded a look at these items to determine how something was made – what kind of joinery was used, construction techniques and materials.

All too often, we have to rely on the individuals or entities responsible for the confiscation of these treasures. Interestingly, in many repositories, including museums and private collections, only a very small percentage of the items (10 – 20%) are ever put on display. After a bit of research, I believe that dovetails are the perfect complement to an African mahogany altar with a Baule door.

In the last post, Altar-Origins, I prepared the wood for the altar cabinet top, bottom, and sides. There are a lot of ideas in my head. I will accept many and reject some, but I know the project will unfold in a wondrous way.

Part 2

Joinery junket

The dovetail question made me dig a little deeper. There had to be joinery of some kind. Were joints like dovetails used at all in African carpentry and woodworking?

Ancient Egyptians and Nubians were prolific producers of furniture and other items that have been documented. Acacia, palm, elm, and various evergreen trees provided timber. Cedar from Lebanon was used the most for larger wood structures.

Do you know what is surprising about this? Egypt had no forests. Desert sands don’t support tree growth. So the first order of business was to source the wood, then the woodworker. Many of the men were day laborers, skilled workers and craft masters who freely sold their services. Many times they were human “spoils of war” captured or offered in battles with kingdoms near and far.

Skilled guild members exchanged knowledge with each other. They passed it along to indentured apprentices and generations of family. Captive men or slaves were often forced by their captors to learn a trade in exchange for a slightly better life. They became craftsman and perhaps even attained a higher status. The ever fragile arrangement guaranteed their lives as long as the work was needed and held in favor.

It is not difficult to believe that these skilled craftsmen ended up all over the continent and Europe via war, diplomacy or simply, escape. Many returned to their homes of origin all over Africa, including the West African coast, with new skills and knowledge. And passed them on.

Joinery tools of the trade

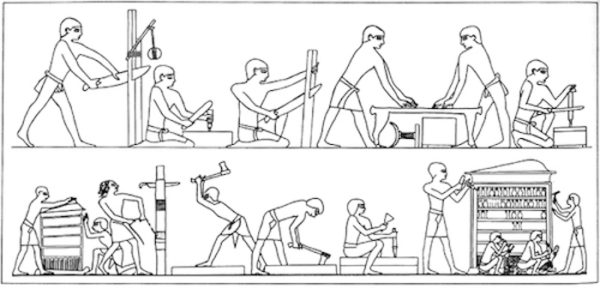

Materials used in the trades ranged from clay and stones to ivory and wood. Some of these materials were obtained from nearby villages. Others were imported from places hundreds of miles away. Tools found in tombs and drawings reveal joinery tools: axes, saws, adzes, chisels and mallets.

Mathematical and geometric calculations to create ancient works still astonish.

There is evidence of joinery such as mitering, tongue and groove and butterfly joints utilized during this period. As civilization advanced, woodworking techniques developed further.

Studies of old furniture from almost every country on earth have revealed a detail, often hidden, that we recognize as dovetail joinery. Almost always it seems to be a surprise that solved a mystery about how, for example, that furniture held together over time. It is even more of a surprise when a dovetail was the secret.

African craftsmanship before colonization

African countries made and traded goods with each other. The ancient Kingdom of Benin controlled and dominated trade for both raw and crafted goods. Trade guilds were sophisticated entities that catered to the king or Oba (all kings were Oba), his family, and associates. Royal items were made to the Obas’ specifications with the finest materials and by the most skilled craftsmen.

Prestige and recognition served as payment for the items. When the artisan, craftsman, or tradesman had time, he made items to sell to the rest of the village. Some were able to conduct trade in other villages if permitted by the trade bosses who were guided by the king’s royal advisors.

Trade goods from West Africa and, in particular Benin, were known. Items were acquired by and in possession of the Portuguese. By this time, knowledge of the superior workmanship evident in the Benin bronzes produced by lost wax casting was widespread throughout not only Europe but in Asia for at least 400 years. The works were highly desired and respected.

Economic diplomacy

The British consistently pushed a derogatory narrative that barely disguised its motives to annex the Kingdom and its resources. Despite this, Benin’s economic and diplomatic relationships with other countries grew. Many of the West African countries benefitted as well. Keen trade practices and diplomacy enhanced and strengthened the Oba’s management and defense of the Kingdom. They knew the influence and power that came from that. They used it well.

The production helped create a network of allies, appease enemies, and preserve the life and legacy of the Kingdom. Tried as they might, Oba and his defense forces could no longer stave off the relentless encroachments which ended with the brutal invasion by the British in 1897.

The Kingdom’s diplomatic and trading partners, in Europe and on the continent, offered no meaningful advice or assistance. They watched, however, and waited.

Asantemanso is called the biggest tree in Ghana – some

would say even of West Africa – with a (current) height of 110 meters or more than 360 feet.

Ghana

Cameroon, Guinea, Equatorial Guinea, and Togo, circa 2014 .

An extensive timber trade existed in Gold Coast Ghana. African mahogany, sapele, wawa, emeri, and other woods were extensively taken out of the Ghanaian forests. British imports of African mahogany began in 1833. By 1897, numerous attempts to take over and “protect” timber lands and assign rights to the Queen of England had been made.

Understandably, there was fierce opposition by Ghanaians and village chieftains affected by these efforts. The protests forced the (temporary) abandonment of the scheme. Later, timber was cut away by clearing the forests to make way for the production of cocoa. It seems that the aim to skim the forest was ultimately accomplished.

Destruction of a Kingdom

Back in Benin, the British invaders found and carried off thousands of expertly crafted bronzes, furniture, and other sacred treasures as what? – “spoils of war”. I would never call it that. They were envious. They questioned how these people could possibly have produced such work. Well that was just the battle cry to justify their actions to come.

They refused to believe what they saw with their own eyes: human beings deserving dignity and respect. Culture building was taking place by black Africans without British permission or approval. The British concluded – had to conclude – that primitive savages – Africans – had no inherent skills or thoughts or intrinsic human rights.

The Kingdom had thrived and maintained a leadership role in West Africa alongside Ghana. Beautiful execution of altar bronzes and other items could never be the work of so-called primitive savages. Sadly, that had been the conventional thinking determined, accepted and promulgated by the so-called civilized world ever since.

Oba and his people fiercely defended the Kingdom from invaders for centuries. Mounting British military losses in the area resulted in jealousy and rage toward the formidable kingdom. The victories cemented the reputation of Oba and his people and, I strongly believe, embarrassed the British.

Not forgotten

Still, the British bloodily “confiscated” these sacred ancestral items after hovering over them and the Kingdom for the many years following defeat after defeat. My thought – my only thought – is this: to whom were they returning the protected – their words – items?

Nothing else was left: Tools?… gone. Master craftsmen?… gone. Accumulated knowledge?… gone. Generations of descendants?… gone. A royal military and cultural complex looted and burned to the ground. And a king forcefully abducted from his land.

Then the rush to plunder, weaken, and destroy an entire continent and its people escalated. And those who watched and waited finally moved in on this important place and its people. The continued assault upon the entire continent by opportunist colonial “powers” for more than 125 years was undeniably immoral. It begs reckoning.

Now that the truth is known, heritage items are slowly finding their way back to their countries of origin.

As the treasures are welcomed back home, I pray that they will impress and inspire the descendants of the creators to continue searching and creating.

I have my answer

Yes, I am going to put dovetails all over this!

______

Next time: the shop altar project continues.

Baadaye.

♥️ Shirley J