During my walk on the Shikoku, the focus was on Buddhism. All of the temples were Buddhist temples with Buddhist monks who practiced Buddhism. Some temples, however, coexisted next to or in the same spaces as Shinto shrines. Syncretism is the word for this cooperation of existence between the two practices or religions. What are they – either or both? It depends on who is talking.

a funny thing

Shinto is the official, national religion in Japan. Schintoism, like many religions of the world, is official because governments say they are.

But a funny thing starts to happen: resistance. It’s resistance by people who make observations about the things they see. That could be hypocrisy, jealousy, greed and graft, ineptitude, abusive authority, illegal enforcement, or other things. Mostly, people grow tired of an unresonsive, unmoving, static, and archaic enforcement of tenets meant to benefit only the privileged few at the expense of everyone else… until the world ends.

Then something new comes along that appeals to people’s sense of wholeness, fairness. and wanting answers and something new.

In the 7th century, Buddhism made its appearance in Japan. People gravitated to this new belief or practice or for some it became their religion. This change, which grew to threaten the influence of the religion at large precipitated a crackdown.

Meiji Period

The Meiji Restoration in 1868 and its accompanying centralisation of imperial power and modernisation of the state saw to that. Or so it thought. Shinto was made the state religion. An order outlawing syncretism was enacted. That was followed by efforts to eradicate Buddhism from Japan.

Attempts to suppress the upstart lead to takeovers or conversions of Buddhist institutions to Shinto, burning and destroying temple properties, fights, and worse.

However, by that time Buddhism was so deeply a part of Japanese culture and life that the government had no choice but to end its harsh stance. Slowly, cooperation and coexistence became the new order. Now the two beliefs exist side by side, on properties but also in the minds of believers.

A large percentage of Japanese people consider themselves non-religious. As a result, many people apply both Shinto and Buddhist tenets in their institutions, homes, and their minds.

Let’s visit a shrine.

Meiji-Jingu Shrine

On the occasion of the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Emperor Meiji proclaimed the Charter Oath in Five Articles in front of the kami (spirits, deities) as the new guideline for building a new Japan.

The shrine was completed and dedicated to the Emperor Meiji and the Empress Shoken in 1920. He was the first emperor of Japan.

The shrine was destroyed during WWII but rebuilt shortly thereafter.

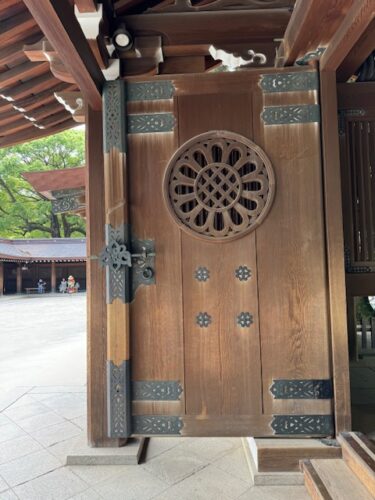

There are three sixteen-petal chrysanthemum-shaped crests decorating the upper lintel. The chrysanthemum crest is the crest of the Imperial Family and indicates the connection between the Imperial Family and Meiji Jingu.

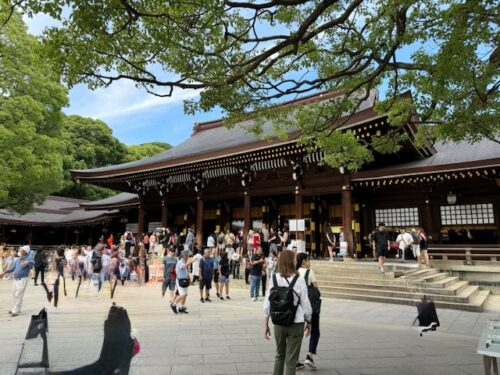

We are in the midst of the city, but you wouldn’t know it. The walk along the long, wide promenade through the forest is overwhelmingly peaceful.

It is quiet. The birds singing draws attention to nature’s wholeness. The giant, ancient trees provide a protective wall against the vibrations of the city.

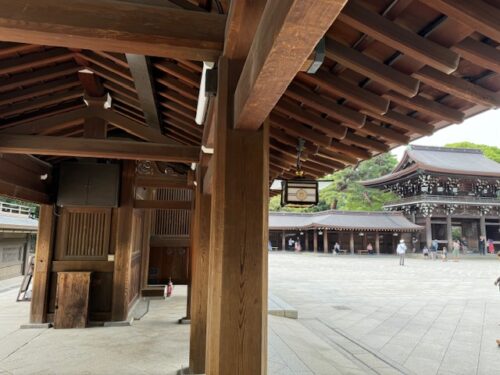

The inner gate

This is the largest wooden myojin style torii of its kind in Japan, standing 12 meters tall and 17.1 meters wide.

The large torii, is built in the same style as the first (stone) torii at the entrance, with curved upper lintels.

This torii has come to symbolize Meiji-Jingu for many because of its impressive size.

Minami Shinmon, Main Gate

Messages written on ema can be anything from pledges to the kami to expressions of gratitude and other wishes.. Messages can be written in any language and by anyone, regardless of faith.

I received a goshuin for my stamp book.

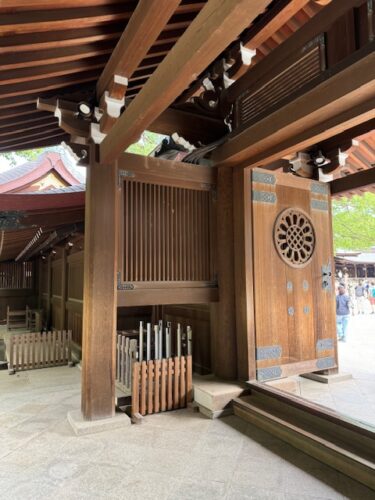

Architectural details

The chrysanthemum motif is see throughout the shrine buildings.

Kiyomasa’s Well, in the temple garden is considered a “power spot,” a location where people visit to receive positive and restorative energy. I consider the entire shrine property as such.

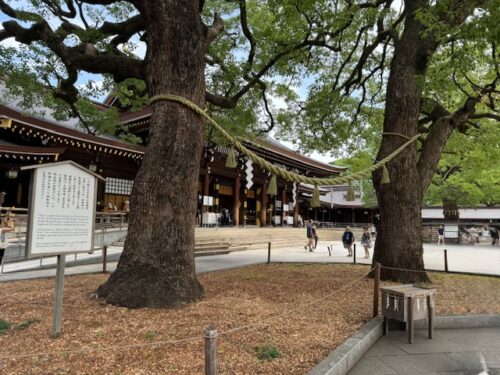

This pair of camphor trees is known as Meoto Kusu, or ‘husband and wife camphor trees’. They are joined by a shimenawa, a rope which signifies their sacred connection. The shimenawa in Shinto is used to indicate sacredness and ward off evil spirits.

Meiji Jingu also offers the sowa mamori, a special omamori (amulet) for luck in love, infused with the aroma of camphor trees.

Shinto weddings are held at the shrine here under the auspices of the tree couple.

The vast grounds of Meiji shrine hosts many festivals and ceremonies. It is visited by foreign dignitaries when they come to Tokyo.

This is the approach back down the promenade to the stone torii on my out of the shrine precinct. Visitors are still coming!

Outside the main gate. An important person must be arriving. Police were in force, setting up security hurdles and clearing the area of wayward people and vehicles.

I’m glad I finished my visit.

One more place to go in Tokyo.

See you next time.

Baadaye and Mata Ne (またね)

Shirley J ❤️

This and several posts this summer chronicled my pilgrimage in Japan where I walked the 1200 kilometer-long Shikoku 88 temple pilgrimage and beyond. Read my announcement here.

2 thoughts on “🌸 Noire Henro-San: Tokyo – Pt 4”

Ahh. I hadn’t understood the distinction between Shinto and “State Shinto” before. I had earlier thought Shinto was pretty intertwined with Buddhism, which sounds like how it was before the advent of “State Shinto” in the Meiji Era.

Thanks for encouraging me to read up a little.

I’m learning about it too. Japan had a fascinating religious, political, and economic history that is worth studying. 🌸🕉️

Comments are closed.