Old tools like the North Brothers Yankee 1003 are irresistible. This hand-cranked bench drill press was patented in 1905. Having seen a handful of these tools in old barns and junk heaps, I want to know how such a tool was invented over a hundred years ago. That is, without computers and high tech assisted manufacturing.

It is even better if I can take it apart, reveal its secrets, and put it back together again.

I gain a great deal of knowledge about many tools this way. It is especially useful in understanding how or why a tool such as this may malfunction.

I found an opportunity to do just that.

In my next life, I want to be a pattern maker

Pattern making is a skill that supports many manufacturing and metalworking processes from the lowly screw to automobiles and planes to rockets.

Early inventions were modeled out of wood by pattern makers who used woodworking skills to fashion parts. Similar to the lost wax process, the model was then used to cast the final product.

A competent pattern maker needed a good eye for detail, an ability to read and interpret blueprints, and flawless execution. Being able to communicate results to designers and engineers is the most important skill of all.

In my other life as a seamstress, I design and make slopers or block patterns for apparel. Grading patterns and, otherwise, tweaking them requires skills similarly needed for industrial pattern making.

Hmm, I’m already a pattern maker!

North Brothers Yankee 1003 bench drill press

The North Brothers Yankee no. 1003 hand cranked bench drill press was manufactured in the early 1900s through the early forties. Stanley acquired the company after that.

The North Brothers were known for the spiral ratchet technology subsequently marketed by Stanley on the Yankee brand screwdrivers and push drills. The 1003 has a big sister: the North Brothers Yankee 1005. Still a bench drill press, the 1005 is bigger and has a compound or double ratcheting mechanism.

Nowadays, a North Brothers bench drill may appear in an old barn or at auction. Often, a drill is found in pretty good shape but the cost to acquire it is steep. The alternative is that the tool was recovered from dank conditions (where old tools go to die) or is in bad shape with seized or missing parts.

The drill has no base to stand on its own. Consequently, it must be affixed to a bench or other flat surface in order to be operated. It seems that damage occurs when an unattached or unsupported drill topples over.

The ratcheting knockoff

One remarkable and consistent piece of damage that I have seen: the ratchet “knockoff” is missing or broken from the top of the drill.

The ratchet fitting or part helps it shift from friction drilling to ratcheting. I believe this drill was actually developed for drilling into metal stock. The automatic operation prevents binding without remedial action on the part of the operator.

The knockoff, if you find one, can cost as much as the tool itself. It is that important. Any knowledgeable tool parts dealer knows just how rare and crucial it is.

I found one

A few years ago, I found a Yankee 1003 drill on the internet. It was intact from what I could tell from the images on the seller’s website. The maker’s badge was missing but that wasn’t important to me. More than a week passed while I waited for the tool to be shipped across the country.

Excited.

My package finally arrived. As soon as I picked up the box, I immediately knew something was wrong. Whatever was in the box was heavy, loose and moving around! I opened the box and found the bench drill inadequately wrapped and… and the ratchet knockoff mechanism –that part – had snapped. It. was. broken.

Not excited.

I was disappointed and heartbroken. First, the seller had a good reputation for competence and care in handling and shipping rare tools.**

Second, that care was not evident due to the lack of cushioning in the box.

Lastly, the knockoff had not been removed from atop the drill nor separately pad-wrapped and secured in the box for shipping.

The drill press body and gears are cast metal or cast iron. I immediately knew that I could not glue the piece together. I thought that maybe, just maybe, I could weld it. Well, I’d have to learn how to weld first, haha!

I called and walked the part around to some welders. That bit of exercise yielded no good results. All told me that it would not be worth the cost to weld or braze the piece.

Again, I looked into brazing the piece myself. However, I didn’t want it to look like a repair. And, I did not want any repair to interfere with the operation of the ratcheting mechanism.

Lastly, I didn’t want to burn my shop down.

Fashioning a new ratcheting hook

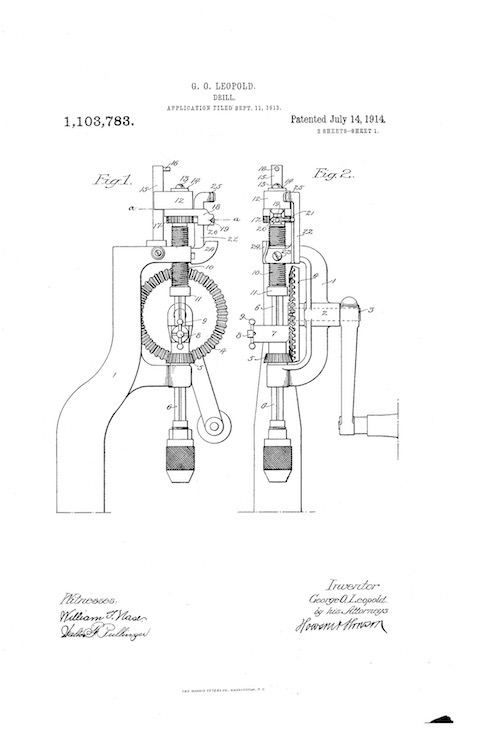

After a period of despair I thought of something. I looked up the patent drawings for the Yankee 1003 and went to work.

Next thought: I could make a new part if I studied it. Then, I cut and shaped a small block of ash.

The longer piece was easier to hold while I shaved thin layers from the wood. I millimetered my way as close to the actual size as I dared to go. I was afraid that I might get just thin enough – too close – and snap the delicate leg of the “L”.

It snapped!

I debated with myself whether I would start again. A little glue on the break could let me see if this part would even work. Well, I glued it together and continued with my experiment. It worked.

Here is the part, lightly coated with shellac, on the drill.

Pattern making? Right.

The North Brothers Yankee 1003 revived

I cleaned the drill a bit and oiled the crank joint ever so slightly so I could turn it. Now I’m ready to roll.

Click video:

And it actually works.

Intuitively, I don’t sense any ratcheting kicking in. I think it is not so much for wood as for comparatively harder material such as metal. It sounded like it wanted to, but the wood just did not call for it. When needed, the ratchet mechanism should subtly kick in. Here I only observed direct drilling… which is still a good thing.

I observed that nothing else happens until I simultaneously pull and turn the fragile upper shaft pin. Note that I am holding my breath while pulling that pin! The pin pointed right or left – the drill will not engage when I attempt to turn the handle. Once the pin is pulled and turned down (or up) again, the drilling continues without interference.

Now I can exhale.

Click video:

That’s all I found. And I didn’t break anything. At this point, it is wise to be satisfied that the drill actually does drill. I don’t think that 100 year old pin should be pulled and turned many more times, though!

Sometimes, those are the results you get when dealing with old tools. As always, I will file away the information I have so far. And… I will keep my eyes open for anything that may further my understanding of this intriguing tool.

– Shirley J

💔

** About that damage to the drill:

I contacted the seller immediately after opening the package. They just as swiftly acknowledged the problem and refunded all of the money that I paid including shipping. Since the tool had travelled a long way we agreed that it made no sense to pay to return a tool that was significantly damaged and thus rendered unsellable. I appreciated the integrity of the seller. This could have gone so wrong, but was resolved peacefully. So, I was able to keep the drill and perform my experiment.

❤️🩹

10 thoughts on “◾️ North Brothers Yankee 1003”

I just bought a North Brothers’ 1003 drill press. Mine is missing the bolt and washer that hold the ratcheting mechanism on to the top of the spindle. I am waiting for the seller to look for the missing parts but I wonder if I could substitute a modern screw and washer to do the same job.

Some tool makers from the era this machine was made used screws and bolts with non standard threading . Does anyone know if North Brothers used standard fasteners?

You may be successful with a modern screw and washer. Try it. Standard vs proprietary materials – that is the question. Sometimes its a matter of finding a machine screw with fine enough threads that enable the machine to work. If the original was a proprietary machine part (yes, even a screw) a substitute makes that almost impossible.

Good luck on your restoration!

Hello Shirley,

If I had the parts they could be 3d scanned (optical process so non-destructive). Allowing others to replicate the parts using drawings.

I have a 1005 which has no ratchet mechanism. It was replaced with a 4”wheel welded to the shaft. So it is cumbersome to use.

Thanks for reading Jim. You have a couple of solutions to this particular problem. I am impressed that you went with welding that pulley on the shaft. It seems that everyone who has run into this tool are constantly on the lookout for a remedy or repair for the knocked off knockoff! Now that we are in 2022, 3D scanning would certainly be a viable option.

Hello Shirley. BTW I did not hack weld the top mechanism. That was the previous owner. 😏

If you want to mail me the cast iron part I can make a copy. First bond it together. Then 3d scan and finally make a metal version. This is all very expensive equipment but I have access to an amazing shop at work.

Researching the possibility of even fashioning a workable “replacement” knockoff from wood was the goal for me. The result was satisfying for my purpose.

I won’t take you up on your offer but thanks for making it.

I remember my dad fixing things like that when I was growing up, we didn’t have H D and Lowe’s back then.

That is the truth! Self-sufficiency was the order of the day.

I love your creativity and expertise, Shirley! Thank you for sharing!

Thanks Natalie for reading about life in my wood shop. The door is always open… you never know what you may find. Regards!

Comments are closed.